She had a dirty sense of humour and a quick wit, and loved sex and laughing at silly things. She was barely 18 when she became Queen in 1837, and her advisors tried to discourage her light-hearted interests out of fear that the public wouldn’t take her seriously. She was stubborn, playful and youthful, and these traits ensured that she was open to new ideas that were exploding around her in science and art - an interest encouraged by her husband Prince Albert.

A brief history of anaesthesia that won't send you to sleep

Early medical experts had two responses to basically any illness presented to them: draining blood or amputation. It’s not surprising, therefore, that they’d long been after a way to relieve a patient’s pain while they operated.

Unfortunately they didn’t yet appreciate the astounding facts being uncovered by clever science brains as anything more than amusing reads. Scientists had been mucking around with different chemicals that worked as anaesthetics – as well as other things – for hundreds of years, because that’s their job.

Laughing gas

For example, in 1772 Joseph Priestley discovered nitrous oxide, which lead seven years later to fellow scientist Humphry Davy apparently having tremendous fun trying it out on himself and animals, eventually noting that it could be used therapeutically.

(Scientists having tremendous fun or dying while trying out new things is a bit of a theme in history.) However, it was mostly used in comedy shows, including one launched by a man who named himself ‘Professor’ Samuel Colt, who used his show to raise money to build the prototype of a revolver...

Think about it as we see weed today. At the moment, it’s mostly a recreational drug to get you high, but it does have medicinal properties. Similarly, no one was interested in this party trick's potential for medical use until a man/dentist named Horace Wells attended one of these laughing shows in 1844.

Wells realised, as Davy had, that nitrous oxide could be an anaesthetic. He found this out in the only sensible way: he had the travelling circus performer administer it to him, realised he felt nothing, and then a few months later got his colleague Dr Riggs to remove his tooth while he was under its influence. Unfortunately for Wells, when he tried to demonstrate it on someone else, the patient cried out in pain and everyone jeered loudly and obnoxiously.

Ether is a gas

A few years before Wells saw more than the funny side of nitrous oxide, scientists were getting interested in ether. Again, they had been aware of how to produce this for a couple of hundred years, but it was a laughing stock among the public. Fortunately, doctors started trying it out and found that - phew - it worked.

The first public demonstration was in Massachusetts General Hospital, where John Collins Warren was scheduled to remove a tumour from a man's jaw. Apparently the man in charge of the ether, William Morton, showed up late but just in time to give the patient a 3 minute dose of ether gas that meant he didn't feel a thing.

From then on, Boston surgeons were all over the ether, willing to try it in other operations as it proved successful at keeping the patient sedated and therefore less likely to panic and end up dead. All of this dabbling with different methods and sharing of ideas means there’s still a massive debate over who anaesthetised who first and how well and who deserves the credit.

Back in Britain

In any case, the first public demonstration of ether as an anaesthetic in the UK was carried out on 19 December 1846 by dentist James Robinson in London. It does seem that some dentists are out to prevent pain. After this was deemed a success, diagnostic whiz-kid Dr John Snow worked out the best way to administer ether so that it wouldn’t kill the patients.

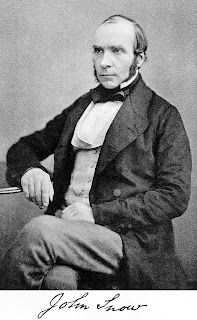

Dr John Snow is a bit of a hero

|

| Not played by Kit Harington |

Snow's main areas of interest were respiration and asphyxia, and the effect gases could have on people, especially in midwifery. After Robinson’s demonstration and his own previous dabbling, Snow developed an inhaler that would administer ether carefully. Like, not lethally. Unlike the Americans, Snow never tried to patent any of the equipment he built, and actually made sure each had clear instructions so anyone could copy it. He was also working with chloroform, which had been introduced to the UK in 1947 by Scottish obstetrician James Young Simpson.

At this point, 34-year-old Snow was the go-to anaesthesia man for London surgeons - a nice step up for a young physician. The non-scientific public was aware of this magical new invention, thanks to both science journals and humorous publications like Punch magazine, including Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Queen Victoria's kids

|

| That's a lot of labour |

Let's keep in mind where she came from: she was an only child brought up by a mother who was more interested in wresting her daughter’s regal powers off her with the help of her manipulative boyfriend than in reading her bedtime stories and playing Barbie.

However, Victoria did like sex. She wrote lots of letters about what she and Albert got up to, including to her Prime Minister, and even got her husband to put a lock on his bedroom door so that all those children weren't eternally interrupting them in the act.

For the first five years of their marriage she was only not pregnant or recovering from labour for 16 months. In 1848 she was pregnant for the sixth time. Prince Albert was a science nerd and had read up about anaesthesia, so he approached her personal physicians about the possibility of using this new-fangled stuff to help his wife during the delivery.

Unfortunately, since it was still so new, they were a bit uneasy about administering it, especially since the only women who had used it so far were not royals, and a girl called Hannah Greener had recently died from the effects of chloroform during surgery. It also didn’t help that a lot of the clergy were against using pain relief in labour, believing women were meant to suffer through it as part of some divine plan. Of course, they were all men.

Drugging the Queen

So poor Victoria had to go through two more births before chloroform’s reputation had improved to the point that it was considered safe and appropriate. It helped that Simpson was a pretty big deal in the medical profession, and Prince Albert had started advocating for chloroform as President of the Royal College of Chemistry. Dr John Snow was called to the birth of her eighth child Leopold on 7 April 1853 to administer chloroform, which must have been a fairly terrifying job. He decided not to use his mask device but a drip and a bit of cloth. Going back to basics seems strange, but in the same way that some people prefer driving a manual car to an automatic, it probably required more work but made you feel like you had more control over the system.

Luckily it was a straightforward birth, if that's a thing, and Victoria described herself as 'satisfied', which is as much as you can hope to be when it comes to labour I suppose. Although medical journal The Lancet was critical of this decision, Victoria called Snow again to the birth of Princess Beatrice four years later.

Snow, in turn, refused to comment on his experiences with her, other than describing her as ‘a model patient’. Of course, one does not slag off the Queen if one wishes to avoid prison and/or a miserable life. One woman even tried to get him to talk by refusing to take the drug during labour until he told her what had happened at Queen Victoria's deliveries. Wily Snow said that he would tell her when she woke up and then scarpered while she was KOed.

Although we'll probably never know the gossip on Queen Victoria's experiences, her Royal stamp of approval was a big deal, and meant that other women could request chloroform in labour. Thanks Vic.

No comments:

Post a Comment